“When Nirvana hit it big, it was overwhelming because we were part of the counterculture. Nirvana didn’t go to the mainstream — the mainstream came to Nirvana.” — bassist Krist Novoselic

By GENE STOUT

“Nirvana: Taking Punk to the Masses” opened last weekend at the Experience Music Project|Science Fiction Museum with the excitement and anticipation one would expect of an exhibit dedicated to Seattle’s biggest moment in rock history — the rise and fall of Nirvana.

But if you were daunted by the prospect of facing massive opening-weekend crowds and what curator Jacob McMurray described as a scene akin to some sort of “weird high school reunion,” perhaps the relative quietude of this week and subsequent weeks will encourage you to visit one of EMP|SFM’s greatest exhibits.

But don’t expect the 3,000-foot exhibit space to be sparsely populated. Nirvana fans will likely be flocking to this display for months to come.

“Taking Punk to the Masses” will be open for business for two years, giving people plenty of time to peruse the hundreds of artifacts assembled by McMurray and his team, with help from Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic and drummer Dave Grohl, as well as the dozens of other musicians, producers and supporters who played roles in the band’s rapid rise to fame in the early 1990s, as well as its sad demise following the suicide of singer-guitarist Kurt Cobain in 1994.

The Nirvana exhibit isn’t flashy, which is a good thing. It feels very personal, reflecting the journey the band made from obscurity in Aberdeen, Wash., to the international stage.

“I really wanted this (exhibit) to be the story of the band Nirvana, not necessarily Kurt Cobain’s story, which gets told all the time,” McMurray said during my private tour of the space before it opened April 16.

“Even though Kurt is a major part of the story, I wanted (the exhibit) to be about the band, but within the context of what was going on in the Northwest. And really what was going on in the U.S. from the early ’80s on.”

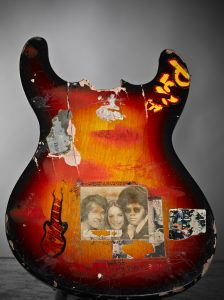

Near the entrance to the exhibit is the Mosrite Gospel guitar on which Cobain wrote the songs featured on Nirvana’s explosive major-label 1991 debut album, “Nevermind.” Another guitar, a Univox Hi-Flyer that Cobain demolished on stage in 1988, carries the handwritten slogan, “WASP — We are scary posers,” reflecting Cobain’s irreverent sense of humor.

A short-sleeve, green acrylic sweater looks unremarkable except for the fact that Cobain wore it for the photo shoot for a Spin magazine cover story in 1993.

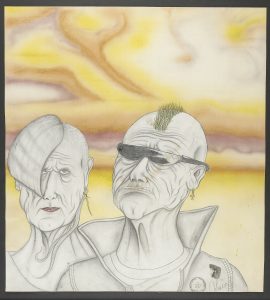

Among Cobain’s original art pieces is a never-before-exhibited high school painting of two aging, Reagan-era punks dubbed “Punk American Gothic.”

A TEAC reel-to-reel tape recorder owned by Cobain’s Aunt Mari was the machine on which he recorded some of his first songs. Visitors can study handwritten lyrics for the songs “Floyd the Barber” and “Spank Thru.”

Nirvana fans can stand in front of the “winged angel” stage prop used on Nirvana’s “In Utero” tour.

There are also scores of candid snapshots of the band’s early years, from its beginnings in Aberdeen to the media frenzy that erupted in Seattle and spread around the world.

In all, there are 200 artifacts and 100 oral histories by such people as producers Jack Endino, Steve Fisk and Butch Vig; photographer Charles Peterson, Sub Pop Records co-founder Jonathan Poneman, early Nirvana drummer Chad Channing and Melvins singer and guitarist Buzz Osborne, among others.

In a letter displayed in the exhibit, Osborne offers a prophetic comment about some of Cobain’s early songs: “I was pretty impressed. Some of the songs are real killer. I think he could have some kind of future in music if he keeps at it.”

One artifact that isn’t on display is a portion of Cobain’s ashes that were offered by his widow, rock singer Courtney Love. McMurray considered the offer, but ruled it out.

“My feeling was that it crosses a weird boundary being in a museum,” he said. “I thought maybe we didn’t want to go that route.”

Novoselic was of tremendous help in assembling artifacts for the exhibit.

“We had about 1,900 objects in our collection related to Nirvana, including about 50 really iconic things and then a bunch of support material — posters, records, etc.,” McMurray said.

“I could have done the exhibition just with what we had in our vaults. But while hanging out with Krist, we went up into the attic in one of his buildings on his property and pulled down these big Tupperware bins, 10 or 15 of them, that he hadn’t looked at in a decade or more.

“We were going through all this stuff and I was going, ‘Can I borrow this? Can I borrow that?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, take it, get it out of here.’ ”

Unusual features of the exhibit include “touch tables” where visitors can view photos and trace the histories of local bands and a “confessional” theater where fans can record their own oral histories of Nirvana experiences.

“I wanted to have a place for people who really wanted to dive deep into the (scene) and learn more about, say, the U-Men or the Blackouts,” McMurray said of the touch tables.

“So we’ve assembled all these stories from various interviews we’ve done. Then you can listen on headphones. Or you can zoom through the assets we have.”

Every section also has a “record wall,” a display of albums popular among punks throughout the United States during a given moment.

“If you don’t know who Black Flag is or Flipper — and there will be a lot of people who don’t — you can get introduced to those bands.”

In the last two decades, there really hasn’t been a scene so closely identified with a single city as grunge was with Seattle. But McMurray is careful to show that other scenes around the country at the time contributed to an emerging sound.

“People outside of the Northwest think that everything came from Seattle,” he said. “So I tried to dispel that myth and show that there were all these little scenes that had their own flavor. They all kind of communicate and overlap.”

A Dave Grohl quote displayed at the exhibit illuminates the link between punk and pop and that helped make Nirvana’s music so compelling:

“I think the lure of punk rock was the energy and immediacy, the need to thrash stuff around. But at the same time, we’re all suckers for a beautiful melody, you know?” Grohl said. “I loved the Beatles when I was a kid, but I loved the Bad Brains too.”

Giving the exhibit a “Northwesty” feel, as McMurray describes it, are wood pieces from a 100-year-old elm tree that was planted in 1901 at the Grays River Grange by Hans P. Ahlberg, a Swedish immigrant and community leader who founded the grange the same year. The tree blew down in a windstorm, and Novoselic, the current master of Grays River Grange #124, supplied pieces for the display.

“It’s such a tangential touch, but it references the Northwest,” McMurray said.

A modest photo of the band in its early days in Aberdeen gives the sense that “these guys don’t have a whole lot of prospects,” McMurray said.

“But in a couple years, they’re on top of the world.”

Find all the details about “Nirvana: Taking Punk to the Masses” at the EMP|SFM Web site.

Among the highlights of my career as pop music critic for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer was writing about Nirvana, from the band’s heady early successes to Cobain’s brutal demise.

Here’s one of my own Nirvana “artifacts,” a link to a story I wrote on the 10th anniversary of Cobain’s death. To read it, click here.